By PAYTON McCARTY-SIMAS

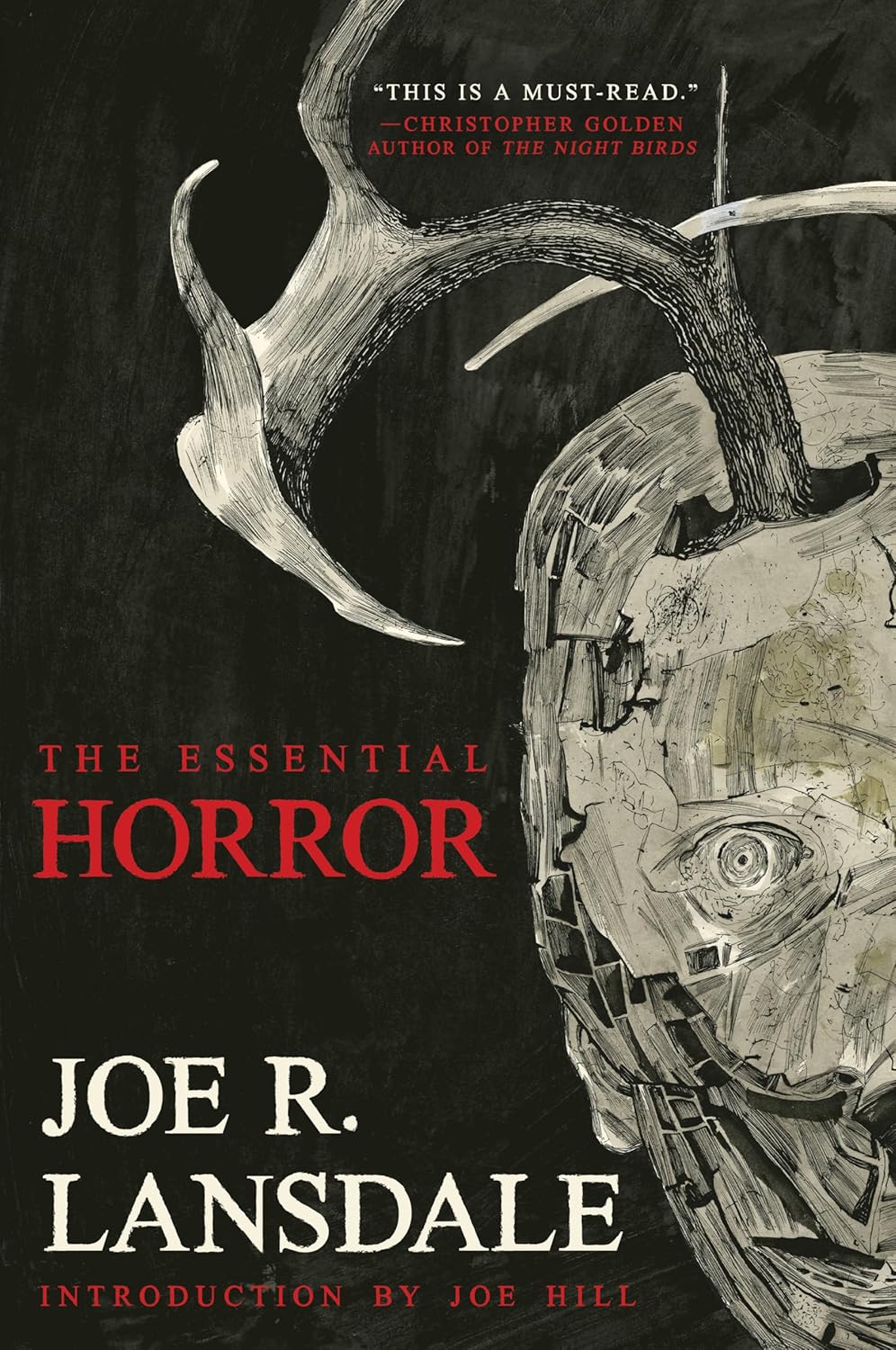

For nearly 40 years, Joe R. Lansdale has been making readers’ skin crawl. The prolific author, sometimes associated with “splatterpunk” (a term he finds justifiably limiting) for his unflinching and blackly humorous approach to extreme gore, has written hundreds of short stories, screenplays and comic books, as well as over 40 novels across a range of subgenres, earning pretty much every horror literary award you can think of in the process. On top of all this, the good-natured Texan even started his own martial arts dojo to boot. To mark the release of his latest anthology, THE ESSENTIAL HORROR OF JOE R. LANSDALE, RUE MORGUE sat down with the author for a fast-paced, wide-ranging conversation about karma, humor, rage, religion and the beauty of a particularly nasty simile.

You published a “Best Of” collection in 2010, and now you have THE ESSENTIAL HORROR OF JOE R. LANSDALE, which you’ve released in collaboration with your daughter, Kasey. What was it like working on this book together?

Well, my editor on this was Rick Klaw, just to make sure he gets his props. But it was great. I’ve known Rick for a long time, and my daughter and I have written all sorts of things together, so it’s been pretty wonderful to tell you the truth. Our family’s close, and it’s nice to have an opportunity to extend that beyond just when they’re in the house. We enjoy our time together. We quarrel sometimes, you know – and I’m usually right [laughs], but anyway, we have a good time.

I loved all of your new descriptions that frame each piece in this collection. How did it feel going back over these stories and reflecting on them?

You know, that was unusual. Some of those stories were from the ‘80s, and of course, I’ve had to reread them here and there for different publications, but this was a whole new experience. I really had a good time because I got lost in the stories myself. I think the first thought I had was, “I’m a better writer now!” [Laughs]. That said, I was very happy with what was there, and I think they were chosen really well. It was interesting to write about them after so many years, too, because I noticed that in some cases, some of my views had changed a little.

Can you say more about that?

In some cases, I felt like the stories were about how “things just happen.” Then, when I look at them now, I think a lot of it is actually your choices: you make things happen. That’s certainly part of life. You can’t control the weather, but there is a certain amount of it that you bring on yourself. So, that was a thematic thread through a number, if not all, of the stories here.

That’s so interesting because one of my questions was going to be about a real sense of a moral code that I felt in these stories. There’s this idea of karma that’s very present in things like “The Hoodoo Man and the Midnight Train” or “Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back.” There are so many images of characters dragging bodies around with them as a representation of embodied guilt – body collecting in “The Folding Man” and “God of the Razor,” soul eating in “Bubba Ho-tep,” dogs’ and people’s corpses being dragged in “My Dead Dog Bobby” and “Night They Missed the Horror Show” and so on. So I was curious about your personal sense of good and evil and how you try to embody your own sense of morality in your stories.

Legendary horror author Joe R. Lansdale

I mean, I’m an atheist, so my views on morality don’t come from religion, per se. It’s certainly around you; you’re impacted by all of these things. But for me, it’s common sense. It’s the feeling of being human yourself and wanting humans to do well, and often they don’t. Also, a lot of the stuff in the stories is real. The dead dog thing, that was people I knew that did that, and I borrowed several things in that story from real life. Fortunately, it wasn’t as dark [as “Night They Missed the Horror Show,” about the lynching of a Black boy by bored bigots], but it gave me an opportunity to speak against racism. When I was a kid, I remember when Night of the Living Dead (1968) came out at the drive-in, there were people who wouldn’t go see it because they heard it had a Black star in it. They were offended by that. Those things stimulated the idea for the story. It was an opportunity, then, to bring in the social issues – and I didn’t try to do it as a preacher. I tried to do it raw, and I tried to do it in such a way that it was offensive and at the same time funny, because the humor makes it darker in the end. People say it’s good to have comic relief from something that dark, but maybe in other ways, the fact that you can laugh at the darkest things that happen to human beings says something else. Mark Twain said that nearly all humor is about somebody being hurt, embarrassed, or killed. When you really think about it, very little humor is benign, and I think that if you can tap into that, you’re actually tapping into the human condition.

Absolutely. On that note, in the intro, Joe Hill talks about how he feels that humor and rage define your stories. He suggests that you write from a place of anger or disgust, and that’s how the humor’s inflected. Do you think that you write from a place of anger?

Yeah, though I think more so when I was younger. You do mellow a little bit when you get older. I’m a person who really loves life and has this hope for humanity. I was a lot more optimistic and idealistic when I was younger, too, but I’ve never lost it. I’m a skeptic, but I’m not a cynic. Still, there are moments when I look at how people treat each other for silly reasons – the color of your skin, your sexual preference – and I think, “Is this really what we need to be doing? Killing each other over whose religion is more religious?”

This whole thing made me crazy angry. Racism, especially. I never really could understand it. I was part of the Southern culture in the ‘50s and ‘60s, and that was just one step above slavery in a way. Black people where I was were controlled by economics and opportunities, of which they had little of either. It was the same way with class. I was definitely in the lower class, and there was a class lower than that! We were poor, but we were doing well compared to some other people I knew. It was all about being better than another group of people: “This makes me superior because I’m better than them.” You gradually develop this negative social competition, where the people who have money have power and control.

Now, I don’t think that all people are like that. I have friends who are incredibly rich, who are some of the kindest, most generous people I know, and then I have people I know that don’t have a pot to piss in who are some of the meanest sonofabitches that ever squatted to shit over a pair of shoes. I guess I don’t necessarily feel that people are good, but we all have the potential to be. So yeah, it all makes me angry.

You can feel that anger in how you play with religion in these stories, too. You’ve said you’re an atheist but not anti-religious, and it doesn’t necessarily feel that way here, but you’ve written in a lot of really nasty nuns and preachers to say the least, right? What’s it like playing with your spiritual upbringing in your writing?

Well, my mother was an open-minded Baptist, if you can believe it. Most people say those words don’t go together, but it’s not true. People are very complicated. My mother is actually the one who introduced me to Darwin and to anthropology, which is a big interest of mine. The symbols and concepts of religion were so embedded within me growing up that when I was about 11, I thought, “I’m going to be a preacher.” Then I read the Bible, and that cured me. I read it all – Old Testament, New Testament – and I said, “This is just like the Greek and Norse mythology I’m reading! It’s like the DC and Marvel heroes!” And when you look at that, you start to realize this cannot be true. The Bible is 4,000 years old, and the world’s a lot older than that. What about the people before that? What was their religion? How did that religion, going through Gilgamesh, become this? I was fascinated with the symbols and power of religion, its ability to create something invisible to control people. Once you notice how all the religions bear a resemblance to one another, you start to see how they’re manufactured.

I feel that very strongly in “By Bizarre Hands,” about a preacher who molests and kills girls with disabilities. In some ways, it’s the hardest story in this book.

Let’s talk about “The Love Doll.” In one of your introductions, you say that your stories are about “bad guys meeting worse guys,” and often that’s about racism as we’ve discussed. But a lot of these guys also have quite a brutal relationship with – and a pretty dim view of – women. You do have one tender and sweet story about love in here, “Not from Detroit,” but coming across “The Love Doll,” a story that you explicitly describe as a “feminist fable” [about a sex doll who comes to life and empowers herself], really struck me.

I have to say that the largest percentage of my heroes are women, and that includes my daughter, my wife, my mother and my mother-in-law, for that matter, who would probably balk at being called a feminist, but she is. When I was growing up, women were very much second-class citizens. I remember that if my mom wanted to go buy something, my dad had to sign for it. She was not allowed to do that. This stuff affected me deeply. The thing is, it’s another one of those deals where I don’t preach to you, I don’t spell it out right away. I make it ugly right up front [it begins from a misogynist’s perspective], and as you go into it, you see the [power dynamics] shift. I try not to be too preachy. I’m sure that, sometimes, it slips out, but I try to go back and actually mark that out when I see it. It’s too easy. We do have a generational shift where people aren’t able to see shadings anymore…

I was going to ask you about that. You mention feeling like people have lost the ability to understand satire in the introduction to this book.

Yeah, I’m bothered by it, but I try not to bend to it. The idea that Wait a minute, you’re not fitting my purity test. Well, the truth of the matter is we’re on the same side, but you’re too narrow-minded or too narrow a reader to understand the impact of what I’m trying to do. Now, whether you like a story or not, that’s your choice; whether you think it’s good or not, that’s your choice. But you have to understand the difference. Look at Mark Twain, one of the most anti-racist writers that ever lived – at least as far as Black people, not so much when it came to Native Americans. Still, you read Huckleberry Finn and talk about an anti-racist novel! He was writing from the perspective of a kid who lived then, who spoke like people did then, but it’s the undercurrent, the satire, that gives you a whole different platform. He was trying to write in such a way that people could relate to it, and yet, he was able to have these dynamic moments when he showed the humanity of everybody. So, I think when people say we want to redo this and take out certain words, they’re missing the point. They’re missing the power, you know? The word itself gives you an impression of how things worked then, which gives you another impression of how far we’ve come. We still have a racist society, but it’s nowhere near what it was. Obviously, you can tell that growing up with these things impacted me. They gave me a feeling of anger, and it bothers me when you have people too reluctant to read something and say, “What is this about? Why?”

What do you think the benefit of writing from these really brutal perspectives is in terms of satire? There are different styles, too. My first thought was Brave New World (1932), where the central characters are so innocent, and through that innocence, you get that same shock.

I like that book. In some of my stories, there’s that kind of innocence, too. Some of these characters, even if they have racist views, for example, don’t really know what racism is, right? It’s baked in culturally. I look back on that time, and I think there are lessons to be learned, but some people refuse to learn them. I see it right now. I see racist rhetoric embraced. I see men who have this almost prehistoric idea that women are there to cook, have sex, take care of things and make sure they’re happy. I’m offended by all that. But that ignorance, that anger, connects with all of us. We all have moments when we’re racist. We all have moments when we’re mad at the other sex. These are things embedded in the subconscious. It’s how you live your life, how you learn from these things that matters.

I think when you write from that perspective, you put yourself into it and face it, and that’s why some people are so uncomfortable with it and say, “Well, I don’t think like that.” You’re supposed to realize there are people who do, and you’re supposed to realize that you, too, are capable of it. When you write, you’re everybody in that story. You’re the hero, you’re the bad guys, you’re the dog that barks in the nighttime. I’ve always tried to think of myself as a positive light in the universe, which is somewhat hubris, I guess, but I’m trying to ask, “How can I make life better, not only for me and my family, but for others?” Sometimes you can only do so much, but by writing from that perspective, if someone truly takes the time to read you, you can connect human to human. It’s one reason in novels, especially, that I write in first person so much. It invites people to be that person or at least walk in their shoes.

You’ve said that you wrote nonfiction a lot when you were young, and you mentioned in one description here that you wrote an essay on the blues that you might want to publish in the future. Does your personal writing process change from fiction to nonfiction?

Well, it’s like anything else; sometimes it’s easier, sometimes it’s harder. But I write pretty much the same way with everything, and when I find that something’s not working, it’s usually because I’m not being true to myself. I try to write the way I would talk to you. I try to say, “Do I know this subject? Do I care about this subject? Do I have a sense of humor about this subject?” And then I write.

I have a very simple way I work: I get up in the morning, seven days a week, I write for about three hours, and I’m done. I don’t do multiple drafts. I may revise as I go quite a bit in the process, but when I get to the end, I’m pretty much done. When I go to bed at night, I tend to dream most of what I write or put it into perspective in my subconscious, so when I wake up in the morning, and my feet hit the floor, I’m generally ready to go. I get my coffee, take my dog out, go upstairs and go to work. I just try to make it simple and try not to overthink or overwrite it. But I’m consistent.

You said that you hadn’t read a lot of these stories in a while. Are there any images in this book that still scare you?

Concepts. “Night They Missed the Horror Show,” what it’s about still scares me. In terms of imagery, though, I think about “Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man’s Back.” The blooming flowers that are less than beautiful [that grow out of people’s heads and take over their bodies after nuclear fallout] and the sort of goofy 1950s imagery of radiation making monsters. I liked the idea of touching on my childhood interest in those old movies, as well as trying to give it some grounding in this relationship between a man and his wife. The loss of their daughter and the loss of the world leads to the creation of these blooms that represent, to me, a life poorly lived in some ways. That imagery, I think of a lot.

In terms of your influences, you mention a lot of Victorian science fiction authors throughout this book. You also talk about Richard Matheson, but you bring up Algernon Blackwood and H.P. Lovecraft more. Do you think of your stories in a Lovecraftian mold?

Some of them are very Lovecraftian in their influence, but I have such a different belief system in general that it comes across differently. It’s more like borrowing the tools that Lovecraft left. I don’t really like the way Lovecraft writes, but I love the concepts of the stories. I much prefer Blackwood and Arthur Machen and then more modern writers: Matheson, Bradbury, Robert Bloch, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald…

So you like it clean, the prose.

Yeah. I’m not always looking for stark. I like a certain poetry, but what they used to call “muscular poetry.” I guess I like what you would call a modern, at least 20th-century approach. I love Twain, too, because in many ways he was a modern writer. He broke that whole Victorian way of writing and wrote in an American voice, a highly influential thing for me.

You know, I get overwhelmed when I think about all the descriptions I’ve written, but I think my favorite is actually not in here. It’s the opening to my novel The Big Blow (2000): “It was hotter than two rats fucking in a wool sock.” That’s my favorite.

THE ESSENTIAL HORROR OF JOE R. LANSDALE is now available from Tachyon Publications.

Thank you for the shout out but you misspelled my name. When you have a last name like mine, it’s not all that unusual. 😃

For the record, it is K-l-a-w

Keep up the good work and keep spreading the word on horror!

Rick

Hi, Rick!

Thanks for reading and catching that! Fixed your name.