By PETER THORNDIKE

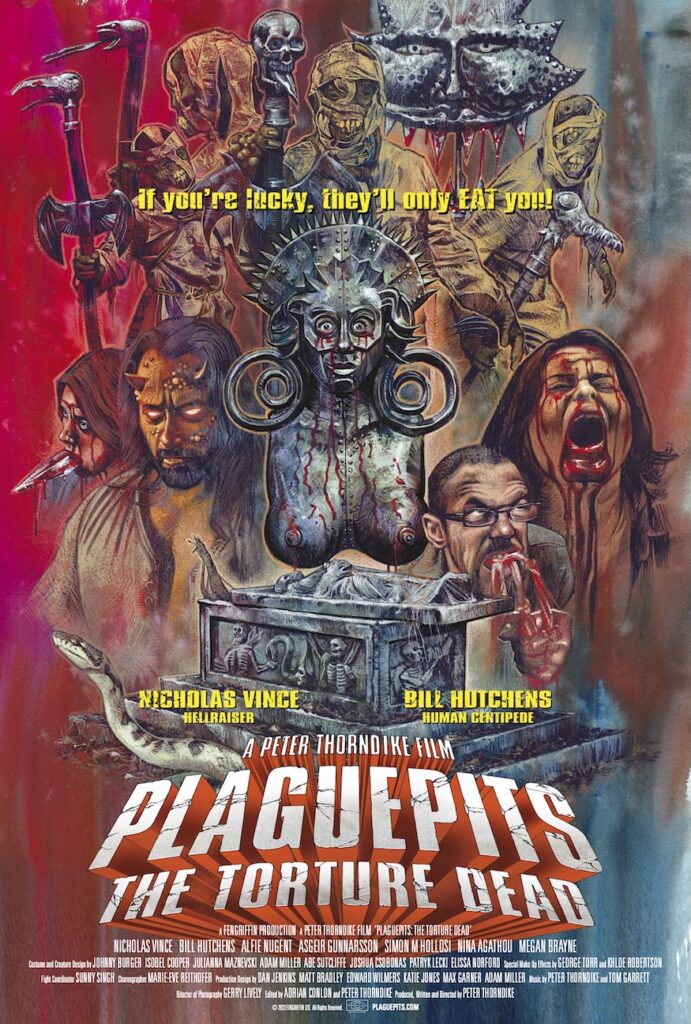

(Ed. Note: Gerry Lively, the British cinematographer whose credits include the third and fourth HELLRAISER movies, the WAXWORK duo and RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD III, passed away on November 7. Below, he’s remembered by filmmaker Peter Thorndike [pictured above left with Lively], who collaborated with the DP on PLAGUEPITS: THE TORTURE DEAD, an upcoming feature starring HELLRAISER’s Nicholas Vince and THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE’s Bill Hutchens.)

Gerry Lively is one of those horror movie legends from the golden days of the 1980s and 1990s whose work defined the look and feel of an era.

Think of great scenes from the classics of the period. Think of the bloody resurrection of Pinhead in HELLRAISER III, where a naive clubber is unwittingly seduced into giving her lifeblood to the Pillar of Souls in a sleazy club back room. Think of the equally bloody–yet disturbingly, cloyingly beautiful–scene from HELLRAISER: BLOODLINE where a beautiful girl is flayed during a decadent feast in 17th-century France to give the puzzlebox its lifeforce. Think of Jeffrey Combs, as H.P. Lovecraft in NECRONOMICON, searching for the titular book in a shadowy and surreal library. Or sinister host David Warner, showing unwary guests around his WAXWORK.

These movies were all lensed by Gerry, with his signature brand of haunting atmosphere and painstaking attention to detail. He worked with light like a mischievous, Machiavellian magician: conjuring dreams out of thin air.

There was no doubt in my mind about who I wanted for director of photography on my debut feature PLAGUEPITS: THE TORTURE DEAD. It had to be Gerry Lively. I’d acted as my own cinematographer on my short films/music videos, and I think I did reasonably well; after all, I’d actually won an award, a while ago. But I knew my first feature needed someone with greater experience and expertise in the area.

So now came the challenge. Actually getting him.

I had been told that he had become reclusive. I had been told he was virtually retired. Wary of so much of the dross he was regularly offered.

“You’ll never get him,” someone said. “It’ll have to be a pretty special script.” “That’s OK,” I said, “I’ve written one.” The raw currency of every first-time writer/director ever: blind idiot bravado.

But it seems my faith in myself wasn’t totally delusional. Gerry read the script. Loved it. Signed on.

We were in business.

But what would it be like to actually work with him? During our numerous calls he’d seemed fine. But could someone nicknamed The Prince of Darkness due to his almost supernatural way of manipulating light and shade be the pussycat he appeared?

I’d heard that he didn’t suffer fools. That he could, as an old gaffer of his said, “chew heads.” That’s OK, I reasoned. I’m no fool. And I would imagine that my head would be pretty indigestible.

When the time came, Gerry proved to be an absolute dream. He was one of those rare professionals who could perform technical miracles at a moment’s notice as if he was going for a morning stroll. And his ability with people was no less magical. Always charming, sweet and light of touch. I saw his very genuine gentleness and warmth leave smiles wherever he went.

He was never angry, never raised his voice. He didn’t have to: Everyone recognized genius when they saw it.

There were times when he had an idea for a shot or scene which were slightly different from my original conception; always, his version was the better one. A lesser talent–a lesser man–would have felt the need to stress their experience, their status, over mine. Not Gerry. When he gave his advice, he unfailingly did so in the most tactful and unobtrusive of ways. Gerry didn’t have an ego. He didn’t need one. He knew how good he was.

When PLAGUEPITS wrapped, Gerry told me his sadness was threefold. He was sorry that an enjoyable shoot was over; sorry that he was to return to drought-stricken LA after a brief sojourn in the picturesque and very-far-from-dry English countryside; and sorry that our comradeship needed to be interrupted.

For we had been constant companions for the duration of the shoot. After the cameras stopped rolling, we’d hung out, strolled round town, enjoyed lunches and dinners together, taken coffee in the numerous cafes in the area.

And, amidst the endless ruminations on what had gone wrong and right on this or that day’s filming, we were already earnestly discussing our next project. We had bonded so effortlessly and happily that follow-up films seemed inevitable.

We kept in constant touch during the postproduction of PLAGUEPITS, and amidst the editing and fine-tuning, I’d written two further feature screenplays that Gerry read and liked. One in particular–a zombie picture that’s a loose sequel to PLAGUEPITS–he was keen to press forward with. So, schedules were discussed, locations considered. I began thinking of the cast.

As we now know, those projects will sadly never be realized. At least, not with Gerry as my ally. The only thing more fickle than the fortunes of filmmaking is Fate itself. Such is life.

But, I shall look resolutely on the bright side: Prince of Darkness though he emphatically was, this was very much Gerry’s philosophy.

I met a great artist. I made a great friend. And the film we crafted together ain’t bad either.

Gerry Lively: Artist. Friend. Legend.